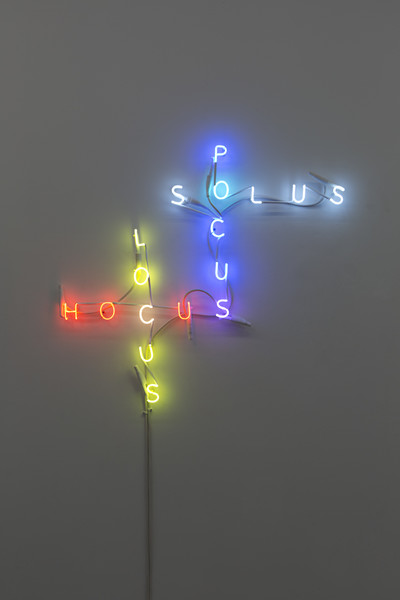

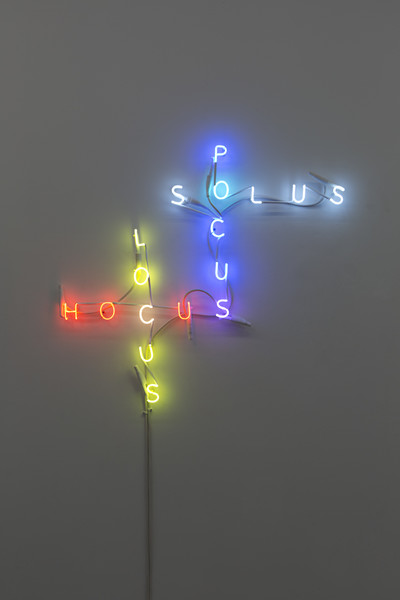

The idea of art is to be as free as possible… . I retain the right to do whatever I want.

—Douglas Gordon

Born in 1966 in Glasgow (Scotland), Douglas Gordon lives and works in Berlin, Glasgow and Paris. His practice encompasses video and film, installation, sculpture, photography, and text. Through his work, Gordon investigates human conditions like memory and the passing of time, as well as universal dualities such as life and death, good

and evil, right and wrong.

The formula, Hocus Pocus, choosen by the artist in his neon work is used by magicians and illusionists to divert the attention of spectators during their manipulations. More frequently used in the Anglo-Saxon languages, the

expression Hocus pocus took in slang, since the XVIIth century, the sense of deceit, swindle, scam. Simplified, it is at the origin of the word hoax. It is also a wink to the surrealists among which the French writer Raymond Roussel whose novel Locus Solus, by the imagination that unfolds there, is likened to a science fiction book.

Gordon’s oeuvre has been exhibited globally, in major solo exhibitions including the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin (1999), the Tate Liverpool (2000), the MOCA in Los Angeles (2001 and 2012), the Hayward Gallery in London (2002), the National Gallery of Scotland (2006), the Museum of Modern Art in New York (2006), the TATE Britain in London (2010), the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (2013), as well as in the Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris (2014). His film works have been invited to the Festival de Cannes, Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), Venice Film Festival, Edinburgh International Film Festival, BFI London Film Festival, Festival del Film Locarno, New York Film Festival, among many others. Gordon received the 1996 Turner Prize. In 2017, he presented I had nowhere to

go at Documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel.

Marcel Duchamp (France, 1887- 1968) has radically transformed the art of the 20th century. In the nineteenthirties,

with the invention of the ready-made– a piece that the artist finds “already-made”, and selects for his

aesthetic neutrality – he paves the way for the most extreme avant-garde approaches. This extraordinary portrait of Duchamp in tonsure was taken in Paris shortly after his return from Argentina in 1919. His dada gesture, prompted in part by an infestation of lice in Buenos Aires, undoubtedly had anti-clerical nuances, since shaving a part of the head is a rite of passage for young men aspiring to Roman Catholic priesthood.

As surrealist companions, André Breton and Marcel Duchamp have collaborated several times. In 1937 for exemple,

on the occasion of the opening of a gallery by Breton at 31 rue de Seine (Paris 6), Duchamp designed the entry as

a friendly contribution. André Breton described the Gradiva gallery as a space with “a glass door made by Marcel

Duchamp, whose opening is shaped like a rather tall man and a visibly smaller and very thin woman standing side

by side.” On this model will be sketched The Announcement for the exhibition, in 1968.A fetishist and transvestite artist born in 1900, Pierre Molinier created astounding self-portraits – until the

year 1976 when he committed suicide by shooting himself in the mouth. Painted or photographed, extremely

sophisticated in both staging and technique, his works of art span the entire spectrum of self-eroticism.

Photography especially is what allowed Pierre Molinier to assuage his hermaphrodite fantasies and create himself

both a new body and a new identity. By means of self-staging, travesty, cut-outs, collage, superposition and

special effects, Molinier portrayed himself as a hybrid and unisex creature, man-woman in one body and one

soul, in black and white self-portraits that are as intimist as they are immodest. We often find the artist naked, his

penis erect or hidden between his thighs, wearing a mask, basque, falsies, garter belt, stockings and high heels…

And so Pierre Molinier’s photomontages and pictorial works of art abound in inextricably intermingling bodies

and limbs that are made up and accessorized.

Pierre Molinier’s work is now even more topical than ever, to the extent that it touches on different veins of

travesty, self-staging, fetishism and questions of identity and genre.

A key figure in body art in France, Gina Pane (France, 1939-1990) established her reputation in the 1970s with

strongly symbolic “actions”. From the emotion provoked by the injury to which she subjected her body while the

‘anaesthetised’ viewer looked on, to the enthusiastic critics who followed her radical acts, Gina Pane constructed

a myth. The question of the sacred, one of the essential underlying threads, far from belonging to the final period

alone, has fed every formal variation of a career punctuated by inventive proposals: geometric paintings and

Structures affirmées [Confirmed structures] (completed 1967), in situ installations and outdoor actions (1968-

70), public actions (1971-79), and Partitions (1980-89).

Inspired by the Italian word “partizione”, the Partitions are symbolic artworks produced from very diverse

materials. Her artworks, which titles are being of particular importance, took her into the realms of sculpture

and installation, evocating a now gone body. The Partitions allows Gina Pane to transfer on the material (glass,

copper, wood, etc.) her body’s experiences through fire,milk, or razor blade. This work strongly evokes the

action Transfert [Transfer] (1973), where a glass of mint cordial and a glass of milk placed on a tablet occupied

the centre of attention. The glass of mint was placed beyond the artist’s reach. Frustrated by not being able to

consume both, Gina Pane ended up breaking the glasses and lapping up the mixed liquids from the floor, injuring

herself with the shards of glass.

A metaphor for an interior conflict whose ‘ins and outs’ we are ignorant of, this action is re-enacted in Dehors

You are using an outdated browser.

Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.