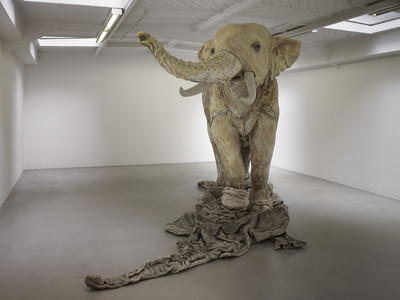

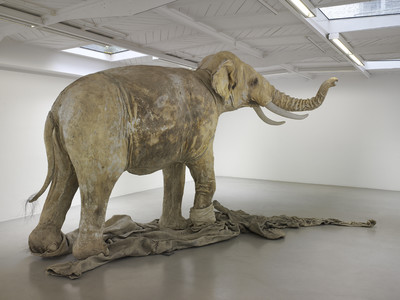

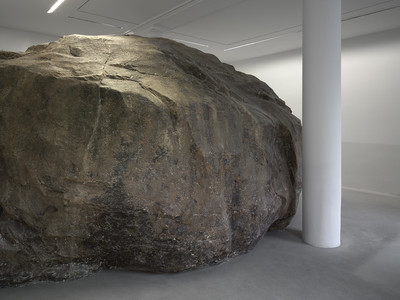

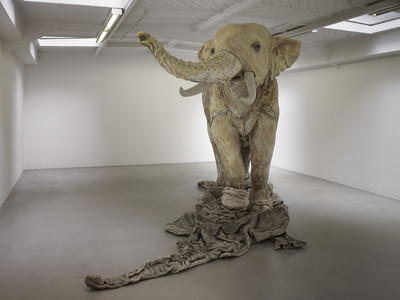

Before settling permanently in France, Huang Yong Ping was already focussing ceaselessly and with a critical eye on the ambiguity of the social function of culture, first in China and later, following the international progress of his work. Seizing on the profound forms and beliefs of East and West, he shows their potential for fascination and violence. Since his days as a radical neo-Dadaist provocateur in China in the early-80s, he has undertaken, with the same determination, a powerful,

politically-charged questioning of our certainties.

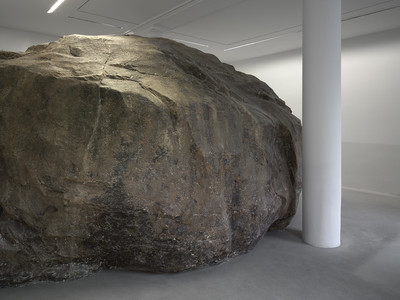

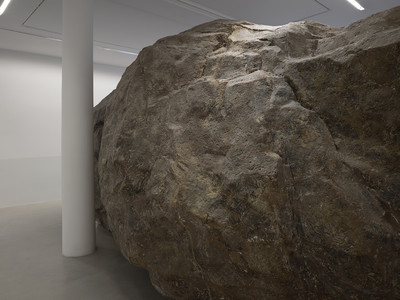

He has seized, this time, on...

Read more