Kamel Mennour is pleased to present ‘L’Écriture des lignes’, Zineb Sedira’s fifth solo exhibition at the gallery.

Earth is Zineb Sedira’s main subject: earth as territory, as habitat, as a part of the world. This is where she looks for inspiration to help her understand the relationship between humans and their environment. For this exhibition she has been considering the place of the individual in the midst of the world by interrogating the meaning of an individual’s practices, inviting us to reconsider, in Heideggerian terms, our ‘being-in-theworld’.

This reflection/proposition echoes a growing interest among historians, anthropologists, geographers,and archaeologists in the means of translating the relationship that this or that society, or fragment of a society, has to the world, nature, its environment, and consequently to its time, past, and history. From this comes the question of how to consider the systems of representation that flow from this relationship. Is it possible to think of territories that are not landscapes, landscapes that do not constitute territories1?

The current exhibition explores this dialectic by interrogating the way in which a society can materialise its territories. For this, Sedira looks at two societies and the relationships they have to their surrounding worlds: Lapland and Algeria. In Lapland, on the banks of the Tornio River, the artist has translated into images the wild, white power of these territories haunted by myths and fables. In Algeria, in the intimacy of family holdings, she evokes beneath the peaceful surface of the photographed landscapes the ambiguity inherent in the way representation revolves between ‘interiority’ and ‘physicality’2.

‘Hic sunt leones’—‘Here live lions’—wrote the Ancient Romans on the unexplored regions of their

planispheres. What should one inscribe on the maps of the distant, icy territories of Lapland? The territories of Lapland have preserved an air of terra incognita. More explored than conquered, the harshness of the climate has to a large extent guaranteed their preservation. Today they constitute one of the last large stretches of wilderness in Europe, traversed by the long Tornio River. This river, this interior line cutting across Lapland and separating Sweden from Finland, is a line of water 730 kilometres long that disappears under ice in the winter.

As she listens to these mysteries and frozen immensities, Zineb Sedira is attempting to discover the echoes of this world, the mute beauties of these landscapes. She offers up petrifying dreams. She gives birth to fugitive images of frozen, clear, brilliant waters, but also dark depths where fantasies and imaginary projections lurk.

To get there, she uses points of view situated at different levels, from the microscopic to the macroscopic,taking into account all the wealth of these hidden spaces. With these images Zineb Sedira appears to create a correspondence with the heavens. Certain details are like stars generating new constellations. A feeling of cosmic totality emanates from this deep background she has exposed, and as a result these forms—these frozen solitudes—encourage us to reconsider the balance between the heavens and the earth, water and sky, earth and water, earth and individual. By way of their poetics they become so many discoveries of the world and of the self. From out of this rich and varied experience Zineb Sedira suggests a relationship that would be in symbiosis with the world, a symbiosis that involves neither fusion nor disappearance. Instead, it is a question of finding resources in the world for rethinking our relationship with nature, a relationship in which we would be neither separated nor united with it, but taking care of it.

With this work, Sedira is asking herself about the whole of our existence. For her it is not a question of demarcating a border between humans and their environment. The two are inextricably interwoven. Accordingly, she highlights the diversity and the subjectivity of the different gazes brought to bear on the representation and the experience of a territory. Blind to both the infinitely large and the infinitely small, the perception of the world she describes takes place on the group and individual level. What stakes, what constraints, what limits are involved in the representation of a territory or a property? How does one outline the geographical form of the land? Faced with such questions, Zineb Sedira becomes aware of the fragility of her representations, together with the fear of losing her father, witness to a cultural and oral heritage on the point of disappearing. With this instance of her father in Algeria in mind, she has looked at how to translate the role of such a memory, at once individual and collective, alive in the lineaments of a territory.

Filming her father walking over his property, Zineb Sedira questions as she goes a territory’s different forms of representation. Is it legitimate to want to define the limits of a territory, or does this amount to removing them from the only domain where they can become fulfilled: the interiority of the one who expresses them, in this case her father? And if this is the case, how, in a respectful way, to map the notion of territory?

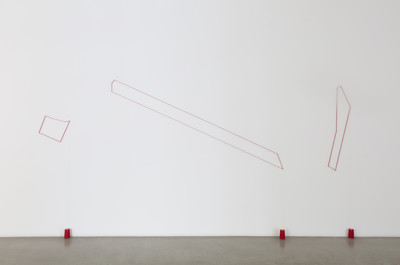

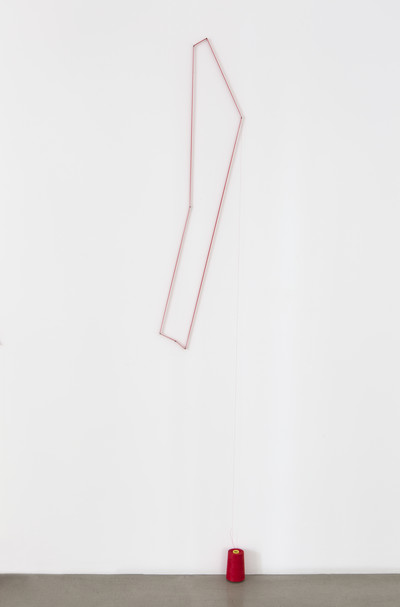

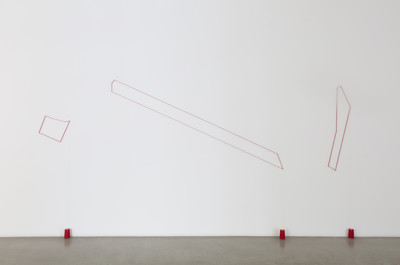

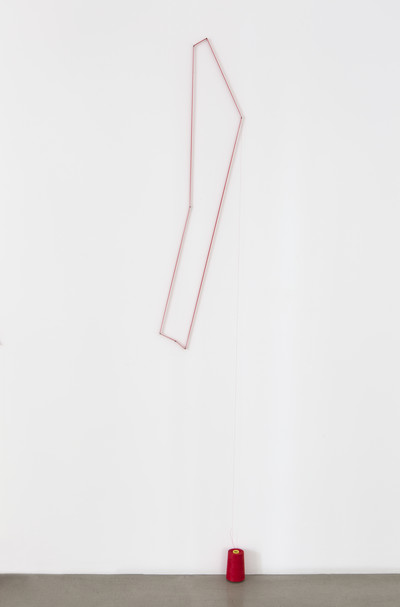

Every effort of spatialisation is, for her father, at once mental and physical. Walking, her father traces out his land both mentally and physically. Experience plays a fundamental role in the tracing of a territory. Zineb Sedira plays with this divide between ‘interiority’—the mental apprehension of the world—and ‘physicality’—the physical materialisation of a territory. Is not the notion of territory inseparable from the experience of the body? The two heterogeneous notions of body and territory seem here, in the experience of her father, consubstantial with the representation of land. A perception of territory at once precise and hazy emanates from such a standpoint. In the space of the exhibition this neither picturesque nor sublime landscape, as it

appears in both photographs and films, finds itself face to face with the typology deployed by geographers and urban planners, which fixes the limits and contours of a territory following precise geometric forms. In this way Sedira displaces the divisions between societies, between cultures, between regions of the world.

Hers is an attempt to understand the thought proper to each of them, to understand it without adopting it. From one land to another, from one world to another, she stops explaining so that she can listen. She places the earth itself in a subject position, risking a reconsideration of its forms and limits, evoking, in this very risk, the different ways a being can consider her environment.

You are using an outdated browser.

Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.